Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

It’s cold outside.

If he concentrates, he believes he can see the paint peeling from the walls of his room, in the spaces between the 30.48 cm square photographic images positioned with geometrical precision and affixed to all four vertical surfaces, floor-to-ceiling, hundreds of copies of the same four images.

The windows, too, are adorned with these images, arranged in such a way as to leave no transparent surface uncovered.

The light fades outside; inside this room it’s always night.

He wonders what he’s doing in a room like this, a crumbling studio apartment in a ramshackle house on 19th Avenue, between Judah and Kirkham, in San Francisco. Surrounded by these images.

And just for a second, he thinks he remembers where and when this began.

*****

The alarm seemed to sound for days inside the cavernous bedroom in the turreted Granada Hills mansion before he was able to reach through the sedative fog to silence it.

Lying on his side, he couldn’t recognize the man and woman smiling out from the framed photograph adjacent to the clock on the bedside table, although he knew exactly who they were.

He had dreamed of another man, a man whose mind was decaying, 595 kilometres to the north.

*****

He had come to live in fear of himself. Accordingly, he had removed the mirrors from the room. When it was absolutely necessary to venture outside, he did his best to avoid all reflective surfaces. He stared straight ahead as he passed storefronts and parked cars. He kept his eyes trained on the floor whenever he needed to open glass doors.

Over the past decade, he had been plagued by a recurring dream. He dreamed he had been in a car crash. Or was it a war?

It was a car crash. He had become absolutely certain that this is where it began.

He had felt safest in cars. Until then. Until the morning a red TVR Cerbera rear-ended him at a four-way stop in Granada Hills, propelling him into the centre of a fortunately empty intersection.

The impact of his forehead on the steering wheel had drawn a small amount of blood and caused him to lose consciousness for twenty seconds.

When he came to, the other driver was leaning in at his open window, apologizing profusely, assuming all responsibility and offering to call an ambulance. He waved away these concerns, distracted by a feeling of familiarity as he gazed up at the man’s face: the intense yet affectless expression, the vaguely porcine nose, the irregular, slightly protruding upper front teeth, the spikey raven-black hair. And the nasal intonation of the voice.

After they had exchanged insurance, license and registration information, he reassured the other motorist that he felt fine and requested a selfie, which he later had enlarged, printed and framed.

He kept the photograph on an upturned packing crate next to his mattress. He looked across at it now. He recognized the man, so familiar from years of record covers, music videos and press coverage; over time, however, he had ceased to recognize himself, although he remembered the occasion of the photograph.

*****

His dream of the man whose mind was decaying was a recurring dream. It had been visiting him for what felt like years. The more he thought about it, the more convinced he became that it dated from the time of a minor car accident he’d had near his home.

Ten years ago, distracted as he hurried to his first cosmetic-surgery procedure, he had driven into the back of an orange Ford Pinto. The driver had sustained a small laceration on his forehead but maintained that he didn’t require any medical assistance. They had exchanged insurance information and, their respective vehicles still roadworthy, had resumed their journeys. The man had been a fan, he recalled. They may have even taken a photo together.

The dream had increased in frequency, intensifying, becoming incrementally more vivid, more elaborate with each iteration. Although he had initially dismissed the notion as absurd, he was now convinced that this increased dream activity was somehow linked to the successive cosmetic facial and dental procedures that he and his wife had elected to undergo.

With each procedure and each new version of the dream, the setting became clearer: the man was often lying on a mattress, in a miserable, windowless room, a rough wooden box to the right of his mattress serving as a bedside table. Every surface of the room, except the floor and the ceiling, appeared to be plastered with large, square-shaped pictures, which had eventually come into focus, revealing themselves as the covers of his first four albums.

Initially impossible to discern, the face of the man in the room had also gradually assumed form. With some alarm, it started to dawn on him that the man’s features were his own, albeit his features from a time before he and his wife had embarked on their odyssey of cosmetic renewal.

Nevertheless, throughout the slow reveal, unfolding over the years, he always felt there was a crucial fact that the dream was withholding from him. There was no evident trace of it in the dream image itself; rather, he simply had the sense that something was missing, that an element was eluding him, always escaping back into the night. In time, however, it began to appear, first manifesting as a dark, undefined space on the upturned wooden box, an object refusing to declare itself fully.

Until the day of his twenty-third procedure.

He had retreated to bed, lulled by narcotic medication, fresh surgical dressings on his chin. He fell asleep quickly and the squalid room appeared in his mind’s eye: the man, the mattress, the box on the floor next to the mattress, the record sleeves. On this occasion, the blind spot in the dream-image was no more. In its place stood a framed photograph, more accurately a selfie. He was unsurprised to encounter himself in the photograph.

*****

It had been three years since he had last contemplated his own image; he had stopped looking when it became clear that the process was inexorable and irreversible. He knew that if he were to look, he would encounter the face of another man, a man more than twice his own age. He knew that he would encounter someone who was no longer him at all. At best, he would perhaps find the wreckage of himself.

In the early stages, he had sought medical advice. The doctor at the local community clinic had been no help, speculating initially about the possibility of late-onset progeria, but ultimately conceding that he had no idea and could only refer him to a specialist he could not afford.

If he were to look now, he would see that the transformation had been merciless. The facial dermis had been ravaged with wrinkles and burst veins. An etching of deep lines gave him the appearance of an antique wooden marionette. On a good day, he might have passed for Ronnie Wood. At the first signs of greying, he had taken to dying his hair a shade of black not found in nature, one that emphasized his increasingly ghoulish pallor and only intensified his likeness to Ronnie Wood. His teeth had become horribly discoloured and had assumed the uneven, bucked formation of a teenager’s dentition before orthodontic correction.

As for the rest of his body, it had developed a stoop and a limp; the knee joints and lumbar discs were disintegrating. The stomach had expanded and was losing its battle with gravity.

*****

Under the vaulted bathroom ceiling in his Granada Hills mansion, he carefully removed the gauze pads and considered his face in the mirror.

For the first few years, the diminishing familiarity of his own image had shocked him. Now he had reached a point at which he felt that his reflection was no longer really him at all: cheekbones had appeared and chins had disappeared; his features had become sharply chiseled; his eyes less tired, his nose thinner; his skin tighter, smoother, more tanned. His hairline had advanced and his hair had thickened. Bariatric surgery had returned his hips to him. His teeth were definitely not his own but perfect nonetheless.

We could hear the screaming before we saw her.

People were running up the street in front of her. Away from her.

It was only as we were about to go into the subway station that we saw the woman running straight toward us on the sidewalk.

*

It’s difficult to remember exactly. It began with the man screaming. There was even some nervous laughter bordering on hysteria. That’s what it sounded like to me.

We just thought he was some idiot. Just messing around, really.

But he started calling out for help.

*

She was screaming.

She pulled it out of a bag.

She was screaming and she was waving something in her right hand. I don’t know why, but I thought that it was a wig. She was waving this.

It was as if she was drawing wild shapes in the air with it. As she passed us, I could see that it wasn’t a wig.

She was running fast but I noticed that she had a large birthmark on her left cheek. She had blood on her shoes and her skirt.

*

There was a particular woman who tried to help him. But it was so bad that there was nothing that could be done.

I remember two people who were very brave. They deserve national recognition.

It was the worst thing I have ever seen. There was so much confusion. It was impossible to tell what was happening.

There was a woman who held an umbrella to protect him from the sun and gave him some water. I think she was speaking to him. I did not hear him talk.

*

We saw her near the subway station. People on the street were running from her. There was panic.

She was going into the shops and screaming. She was running in and out.

I saw her run into the café. They say she was screaming “It is all of you.”

*

He was in total shock.

He was not focusing and his eyes were glazed over.

I thought I saw a saline drip. Some tubes.

A lady, who might have been a doctor, brought a huge yellow umbrella to protect him from the sun. I remember thinking that this gesture seemed pointless, ridiculous even. But at the same time, it was a gesture full of humanity.

*

No one tried to stop her.

The security guard at the café ran away.

There were two policemen but they ran away also.

She was shouting “I am your death.”

I ran but I felt such shock that I had to stop and smoke a cigarette, just to try to get my breath back.

*

He was sickeningly pale.

They just kept coming at him time and time again.

It just ended up in a terrible frenzy.

We were trying to keep any children from witnessing what was going on. This was all we could do, really.

I and four other people carried him and placed him in the back of a pick-up truck.

I could see the bone of his thigh.

I could see that he had almost no stomach. I went to the restaurant and asked to call for help.

*

Some people told us that they saw her earlier in the day, going into shops and screaming and waving it.

Some people also said they thought it was fake. But everyone was frightened and no one tried to stop her.

She could be seen on CCTV.

The policemen only tackled her when she started to set herself on fire.

*

We saw that a man was doing chest compressions. He did this for about fifteen minutes. Then he just stopped. That’s when we knew it was probably fatal.

There was no proper equipment, and I couldn’t revive his heart. Despite my best efforts.

My family and I are deeply shocked. This is something we will never forget, for as long as we live, and please remember I am saying this as a surgeon.

I held the man’s hand and stayed with him.

***********************************************************************

(Survey of Buckley’s work, including posthumous releases up to 2001; originally published at Trouser Press 2002. This version was screwed up by the editor, and I wasn’t happy with it. This was often the case with Trouser Press, unfortunately. Until I locate and exhume my original copy, this will have to do.)

Artists who die young tend to become frozen in myth, often because their recorded legacy is small and relatively homogenous, leaving fans to wonder what they would have become. Tim Buckley died at 28 but his story is slightly different from that of, say, Nick Drake or his own late son, Jeff. Lasting less than nine years, his commercially unsuccessful recording career was brief but productive: he managed nine studio albums, plus enough material for numerous posthumous releases. The immense diversity of his work makes it hard to categorize in simple terms — and even harder to imagine the direction (or directions) he might have pursued.

Along with Orange County, California, contemporaries Jackson Browne and Steve Noonan, Buckley signed to Elektra in the mid-’60s. Although he was perceived as a coffeehouse folk singer-songwriter (as was anyone who strummed an acoustic guitar and didn’t do pop covers in those days), that scarcely describes him. Buckley’s 1966 debut album was already shot through with electricity and displayed flashes of psychedelia; by 1968, he had embraced a jazzier vibe that looked beyond straightforward song structures. Nevertheless, he wasn’t content with just pushing artistic boundaries; rather, he crossed them to explore more difficult avant-garde territory, quickly leaving fans and commercial viability behind. In the process he transformed his rich tenor, which had captivated audiences, into a fierce wailing instrument and dropped his laid back ballads in favor of dissonance and rhythmic complexity. Even more surprisingly, Buckley ultimately reinvented himself as a strutting barroom rocker, pumping out gloriously sleazy white funk.

Buckley recorded his eponymous debut in his teens. Not surprisingly, it’s by no means a mature work, and he doesn’t sound entirely comfortable amid the arrangements and production, which are emblematic of Los Angeles in the mid-’60s. Still, this record does indicate Buckley’s enormous potential. Over half the tracks were co-written by high-school friend Larry Beckett, who has a weakness for awkward, mannered lyrics. On “She Is,” for instance, Buckley’s sublime voice belies his youth, but fey pseudo-poetry like “A mischief mystery she plays upon the flute of early morn” does him no favors. Although often excessively romantic, Buckley’s own songs are superior, especially “Aren’t You the Girl,” “It Happens Every Time” (with a sweeping string arrangement by Jack Nitzsche) and “Wings,” a big symphonic pop number that was certainly hit single material. One of the co-written tracks — the smoldering, psychedelic “Song Slowly Song,” with delicate guitar courtesy of Lee Underwood — anticipates the less conventional musical structures Buckley would later explore.

Recorded in summer of 1967, with Jerry Yester producing, Goodbye and Hello was a considerable step forward for Buckley. While it shares some of the debut’s preciousness, it’s less one-dimensional and more ambitious. This doesn’t always work. The psychedelic touches are more pronounced, and there’s a tendency to incorporate Elizabethan motifs, but over-produced numbers like the title track or “Hallucinations” don’t fare too well. Beckett co-wrote five of the ten songs, including the stirring protest “No Man Can Find the War,” but the more memorable tracks are again Buckley’s own. They show him growing, finding his own voice and developing a highly personal vision (particularly “Pleasant Street,” “Once I Was” and “Phantasmagoria in Two”). The standout is “I Never Asked to Be Your Mountain,” an intense epic of competing rhythms fueled by Carter “CC” Collins on congas. The lyrics might be melodramatic and juvenile, but Buckley pushes his five-and-a-half octave range to the limit, and that makes it work. (The song makes passing reference to his son, who eventually performed it in 1991 at a tribute concert in New York.)

Although Goodbye and Hello captured the counter-cultural zeitgeist with its anti-establishment sentiments and psychedelic feel, Buckley quickly distanced himself from that scene and balked at suggestions that he might speak for a generation or catalyze political change with his records. Disillusioned with rock and the music business, Buckley opted to follow his own creative instincts. He and guitarist Underwood gravitated toward jazz, listening to Mingus, Miles and Monk, artists whose influence declared its presence on the near-perfect Happy Sad. (Echoes of Davis’ “All Blues” are unmistakable on the lilting “Strange Feelin’,” and vibes player David Friedman jokingly labeled the band on this release “the Modern Jazz Quartet of folk.”)

Jerry Yester, who overproduced parts of Goodbye and Hello, shared the job with Zal Yanovsky of the Lovin’ Spoonful, and gets the balance right on Happy Sad. It would have been hard to go wrong with this material. Buckley composed all six songs, evidence of a newfound maturity, alone. In keeping with its title, this is very much an album of moods. Apart from the ecstatic, 12-minute “Gypsy Woman,” Happy Sad focuses on the mellower, introspective end of the emotional spectrum. The only electric instrument here is Underwood’s quietly intense guitar, which, along with Friedman’s vibes, adds tone and coloring (for instance, on the atmospheric epic “Love From Room 109 at the Islander” and the yearning “Buzzin’ Fly”). Happy Sad reached the Top 100, capping his albums’ chart success.

Works in Progress, a collection of previously unreleased sessions from 1968, documents Buckley’s evolution from Goodbye and Hello to Happy Sad. Dream Letter: Live in London 1968 is a superb two-hour live set from that transitional period, recorded with Friedman, Underwood and Pentangle bassist Danny Thompson. Full-band workouts of “Morning Glory” and Fred Neil’s “Dolphins” are outstanding, but solo performances by Buckley and his 12-string steal the show; “Wayfaring Stranger” and a rendition of “Pleasant Street” segueing into “You Keep Me Hanging On” are truly spine-tingling. Further recordings from 1968 appear on 1991’s Peel Sessions EP, which was later reissued with additional material on both Morning Glory and Once I Was.

Buckley produced Blue Afternoon himself, continuing in the melodic folk-jazz vein of Happy Sad with the same players, plus drummer Jimmy Madison. Strictly speaking, however, this was not Buckley’s next album. He had already recorded Lorca for Elektra and was due to record an album for the Straight label, which had been set up by his manager, Herb Cohen, and Frank Zappa. Based on what Cohen had heard of the direction taken on Lorca (he produced the album with Beefheart/Mothers of Invention engineer Dick Kunc), he was concerned about the commercial potential of Buckley’s debut for Straight and asked him to record something more in the spirit of his earlier work. Buckley’s heart wasn’t really in it as he had already set off on a new creative path with Lorca but he complied, quickly recording songs he had already written and worked on in sessions but had not committed to vinyl. Remarkably, some of these tracks, which Buckley had pretty much discarded, rank among his finest: “Chase the Blues Away” and “Happy Time” (both of which also appear on Works in Progress), “Blue Melody,” “I Must Have Been Blind” and “The River.” These epitomize Buckley’s aptitude for taking the folk song as a departure point and expanding it, infusing it with elements of jazz to explore new dynamics, stressing mood and atmosphere.

After the detour of Blue Afternoon, Buckley returned to the experimentation already underway. Blue Afternoon was released to a largely indifferent reaction. Lorca followed shortly thereafter. If, as Debbie Burr commented in Creem at the time, Blue Afternoon “[is] not even good sulking music,” then the five-track Lorca certainly gave folks something to cry about. “Driftin’” and “Nobody Walkin’” show some continuity with Happy Sad and Blue Afternoon, but the album isn’t remembered for those songs, if it’s remembered at all. The dark, brooding title track, which began Lorca, marked Buckley’s most dramatic shift yet. He had often emphasized the importance of vocals as an overlooked instrument and focused on that aspect of his music for Lorca. The voice of mezzo-soprano Cathy Berberian on electronic works by Luciano Berio had impressed Buckley and “Lorca” displays kinship with her technique. Buckley’s previous records had attested to his range and his ability to hold notes, but “Lorca” was an attempt to produce something like Berberian’s highly idiosyncratic vocalese, with an unsettling acrobatic performance that eventually went beyond language into wordless shrieks, wails and vibrato crooning up and down the scales. Moreover, the accompanying avant-garde jazz arrangement in 5/4 time (with pipe organ and electric piano by bassist John Balkin and Underwood respectively) showed little interest in tunefulness. The absence of a comforting song structure only made it all the more uneasy for fans expecting something along the lines of “Blue Melody.” The album, a critical and commercial failure, was Buckley’s final release on Elektra.

1994’s Live at the Troubadour 1969 captures Buckley in performance around the time of Blue Afternoon and Lorca and draws songs primarily from those two albums and Happy Sad. Listened to alongside Dream Letter, the live album recorded less than a year earlier, it dramatically underscores the changes in Buckley’s sound. While epic, unbridled renditions of “Gypsy Woman” and “Nobody Walkin’” offer excellent examples of a more improvisational approach, “Strange Feelin”‘ is a distant, far bluesier cousin of the version on Dream Letter.

Despite Lorca‘s poor reception, Buckley pressed on with Starsailor, a record that drew inspiration from contemporary classical composers like Messiaen, Penderecki and Stockhausen as well as avant-garde jazz. Buckley self-produced his most uncompromising album, a work of genius or folly (or perhaps both) that provokes sharply divided reaction. Buckley expanded his instrumental arsenal with Maury Baker on tympani and Mothers of Invention horn players Bunk Gardner (tenor sax and alto flute) and Buzz Gardner (trumpet, flugelhorn). Sustained melodies and “songs” aren’t a priority here — the more challenging arrangements are fragmented and dissonant, set in unusual time signatures. Although Buckley had proven himself as a lyricist with a distinctive introspective vision, Starsailor makes it abundantly clear that he felt words weren’t necessary to communicate. He often forsakes conventional language for glossolalia, conveying a gamut of emotions — from anguish to euphoria and everything in between, sometimes leaping from one end of the emotional register to the other. The eerily hypnotic a cappella title track features Buckley alone — with fifteen overdubbed tracks of his voice.

Elsewhere on Starsailor, freeform pieces like “The Healing Festival” (in 10/4 time) and “Jungle Fire” (in 5/4) at times give the impression that each musician is playing a different song on a different planet, albeit with absolute control and precision. If Starsailor has any parallels in rock, Captain Beefheart’s Trout Mask Replica would be one — especially in its rigorously disciplined madness. While “Monterey” threatens to become a rock song but never quite coalesces as such, there are some conventional moments, one of which provides the album’s highlight: the ethereal “Song to the Siren,” the track for which Buckley is best known thanks to a 1983 cover by the Cocteau Twins as part of This Mortal Coil. (Even Pat Boone recorded the song in 1968, before Buckley himself had released it.)

When he next returned to the studio, in 1972 for Greetings From LA, Buckley bit the bullet, playing the conventional mainstream fare being demanded of him. If it’s true that he felt frustrated by what he saw as the limitations of rock’n’roll with its clichés and formulas, and that he was unhappy with his new identity, it doesn’t show on this album. Far from it, in fact. Backed by a new band (except for Carter Collins), Buckley sounds completely at home, stretching easily from swampy blues to straight-ahead rock, injecting a generous dose of funk into the proceedings. Both musically and lyrically, this is an orgy of a record, dripping with sweat and sex, and Buckley — whose sense of humor is fully evident for the first time here — throws himself headlong into it. With its conventional rock songs, there’s nothing innovative about Greetings From LA. Even so, Buckley’s character is all over it. His impressive vocal range is still obvious on the opening triad of “Move With Me,” “Get on Top” and “Sweet Surrender,” as well as on the string-washed finale, “Make It Right.” These tracks are light years from the abstractions of Starsailor, whose wailing and moaning suggested a pre-Oedipal, cosmic sexuality — this one is much earthier. (Buckley called this album a response to the likes of Mick Jagger, who sang about sex without ever saying anything sexy.) Buckley may have sung in tongues on Starsailor, but “Get on Top” puts a different twist on the concept: “Get on top of me woman / Let me see what you learned tonight /Then I talk in tongues mama / Oh when I love you / Yes I talk in tongues.” Instead of “flute of early morn” and “O whither has my lady wandered?,” “Get on Top” offers “Like a bitch dog in heat we had those bed springs a squeakin’ all day long.” In “Make It Right,” he’s looking for a “street-corner girl” and implores “Come on and beat me, whip me, spank me.”

The radio-friendly Sefronia was cut from similar cloth. Numbers like “Honey Man” and “Stone in Love” provided additional evidence of Buckley’s new identity as funk-rock sack master, but the record is weaker than its predecessor. Denny Randell’s anachronistic-on-impact LA white-soul production, which pours syrupy strings over several numbers, is hardest to digest on poorly chosen middle-of-the-road love songs that didn’t suit Buckley at all: a sentimental rendition of Tom Waits’ “Martha” and a cloying duet with Marcia Waldorf, “I Know I’d Recognize Your Face.” The genuinely soulful ballad “Because of You” and a stellar version of “Dolphins” (featuring Lee Underwood’s only appearance on the album) do compensate somewhat but, overall, this is a bland affair.

Demos of Sefronia songs — some of which didn’t make that album — are on the posthumous Dream Belongs to Me, which also features a handful of 1968 demos that appeared on Works in Progress. Broadcast live as a radio session in 1973 and released in 1995, Honeyman draws largely from Greetings and Sefronia. While he might have been declining on record, Buckley was still absolutely fine live. This album would stand as a respectable epitaph, were it not for Look at the Fool, which ended Buckley’s career on an inglorious note. Although the title track and “Who Could Deny You” stand up reasonably well, the rest sounds burned out and is best forgotten, especially the dreadful “Louie Louie” rip-off, “Wanda Lu.”

Surprisingly, it took until 2001 for a Tim Buckley retrospective CD to be assembled. The two-disc Morning Glory reflects the struggle between Buckley’s artistic goals and commercial pressures. Two dozen of the set’s 33 tracks date from the period covered by the first four records. There’s only a live version of one song from Lorca, and Starsailor is represented by its three most accessible numbers (including two versions of “Song to the Siren”). By privileging material from the less challenging wandering-troubadour and folk-jazz periods, this collection once again suppresses the material in which Buckley was most invested, and for which he tragically failed to find an audience during his lifetime, which ended in 1975.

(Book review originally published at The Quietus, 2009.)

On Some Faraway Beach: The Life and Times of Brian Eno

David Sheppard

(London: Orion, 2009)

“I have a wonderful life. I do pretty much what I want, and the only real problem I ever have is wondering what that is.” (Brian Eno, A Year with Swollen Appendices.)

It’s an ambitious, some might say foolhardy, enterprise to write a comprehensive account of the life and work of Brian Peter George St John le Baptiste de la Salle Eno. If the simple abundance of the man’s names doesn’t deter would-be biographers, then the task of engaging with his work’s sheer diversity probably will. While it’s a complex enough proposition even to say what his work is, the ongoing proliferation of Eno’s areas of interest and activity has only made the job progressively harder; over the years it’s become more and more of a challenge to paint a coherent picture of what he does, never mind to assess how successfully he does it, and this no doubt explains why no one’s managed.

David Sheppard makes a laudable attempt with On Some Faraway Beach. Drawing on his own interviews with Eno and a cast of associates including Bryan Ferry, John Cale, Robert Wyatt and David Byrne (plus a wealth of secondary material already familiar to Eno-spotters), Sheppard tracks Eno’s iterations: from solitary, fossil-collecting, hymn-loving child to balding, lascivious Roxy musician to Oblique Strategist to ambient pioneer to mega-producer to Lib Dem youth adviser, and all points in between. Focused primarily on his subject’s music, this weighty tome takes Eno’s mountainous CV by strategy, the strategy being to identify and follow the aesthetic thread running throughout his heterogeneous work: that unifying motif is Eno’s valorisation of process over product and his emphasis on a systems-oriented approach, encapsulated in the Cageian mantra, “Define parameters, set it off, see what happens.”

Sheppard doesn’t merely recount his subject’s origins by way of background information, serving only as a de rigueur point of departure. Rather, he insightfully suggests ways in which Eno’s artistic practices and the richly varied creative places he’s visited over the course of his career are inextricably linked to formative experiences and, moreover, to the very particular context of those experiences.

Whereas in 1972 speculation had it that Eno came from another planet, he actually hailed from down-to-earth rural Suffolk, but as Sheppard shows, there was more to the small town of Woodbridge than met the eye. The location of Eno’s prosaic upbringing positioned him ideally for a series of encounters that would mould his sensibility. Historically, geographically and culturally, Eno grew up on various “cusps” as Sheppard describes it, tracing lines of continuity between an early sense of in between-ness and Eno’s famously polymorphous personality. For Sheppard, this cusp experience predisposed him to seeking out and traversing different traditions, disciplines and media, all the while cross-pollinating, juxtaposing and hybridising elements gleaned from those encounters – and always with a disregard for conventional, hierarchised distinctions between high and low culture.

Eno was born into a time of postwar transition, coming of age in the mid-‘60s amid radical changes in Britain’s socio-cultural and political identity. Although Woodbridge, with origins in the Middle Ages, was a seeming bastion of good old-fashioned Englishness, in the late ’50s that tradition rubbed up against its other: American pop culture. The presence of American air bases and 17 000 US servicemen in the surrounding area made Woodbridge an improbably happening place, an environment in which a young Eno was exposed to the then-exotic sounds of rock’n’roll and doo-wop, thanks to Forces Radio and jukeboxes in the town’s cafes, filled with the latest 45s to satisfy the GIs. Hearing “Heartbreak Hotel” for the first time made a profound impression on Eno, as it did on a generation of future musicians. Eno, though, was struck by a specific aspect of the recording: its foregrounding of studio artifice, underlined by the unique, tape delay-crafted texture of Presley’s voice – this early example of the studio’s potential as a place to create music rather than just document a performance would find resonance in Eno’s subsequent working methods.

Exterior forces notwithstanding, some of Eno’s initial acquaintance with otherness came from within his family, which boasted a lineage of musicians and oddballs who shaped his world view. None more so than the eccentric, well-travelled Uncle Carl, who nourished a spirit of eclectic inquisitiveness in his nephew with his houseful of books, artefacts and bric-à-brac from around the globe – from suits of armour and swords to illustrated monographs on Mondrian.

Eno’s foundation course at Ipswich Civic College furnished him with a singular arena in which to find a medium and develop an approach to it. Key in that regard was radical head tutor and cybernetician Roy Ascott, whose slightly unhinged regimen was geared towards having new students unlearn everything they knew about making art. (Ascott also played pupils the Who’s “My Generation,” providing Eno with a Damascene moment about the possibilities of marrying art with pop music.) Instead of working towards the production of finished objects, the students engaged in ludic group exercises that were aimed at fomenting counterintuitive thinking, cooperative strategies and generative systems, as well as dismantling hierarchies and eschewing virtuosity in any particular medium. Another tutor, Tom Phillips, gave Eno something more concrete to hold onto by introducing him to Cage’s experimental propositions in Silence – a conceptual primer for the avant-garde that advocated the rich potential of sound (musical and non-musical) and championed indeterminate, aleatory processes over traditional composition and performance. Phillips also counter-balanced some of Ascott’s more anarchic tendencies by instilling in Eno the importance of bringing discipline and rigour to bear on his work. Consequently, at Ipswich Eno began formulating what would be his own core aesthetic principles as a (non) musician, as a visual artist and as a producer: a focus on process, creative problem-solving and an interest in art generated by systems.

In addition to exposing Eno to American composers like Cage, Morton Feldman, La Monte Young and Christian Wolff, Phillips introduced him to the English avant-garde scene; encounters with the likes of Cornelius Cardew, Howard Skempton, John Tilbury, Gavin Bryars and Michael Nyman prompted Eno’s realisation that, while not a musician, he could use sound as his raw material. Things further coalesced when he read about Steve Reich’s tape-recorder compositions, which offered striking examples of sound being manipulated to make “sound paintings.” To Eno this was a perfect example of an art form constructed around systems and processes; he embarked on his own primitive explorations with the college’s two reel-to-reel machines. Sheppard’s account of Eno’s gravitation towards figures such as Cardew and experimental music circles (leading to his involvement in Scratch Orchestra projects and, later, the Portsmouth Sinfonia) makes the case that Eno was part of the late-’60s British avant-garde. His unique contribution to that tradition was his eventual crossover from the high-culture realm into the realm of pop, not so much mixing the two as refusing to accept the distinction between them. Eno was one of the first, and remains one of the few, British musicians to come at pop music from the conceptual perspective of fine art.

Owing to Eno’s myriad sites of activity, Sheppard characterises him as a Renaissance man. That’s not entirely apposite: such a designation presupposes expertise and virtuosity in multiple fields, something Eno lacks and has consistently made a virtue of lacking. Moreover, that metaphor doesn’t quite get at the notion that Eno’s discrete endeavours in each of those manifold areas are not the primary source of his significance; more accurately, his significance lies in the way he combines them as ingredients in a collage. Whether he’s working with people, concepts, media or sounds, Eno’s forte resides in bringing the components together and setting processes and systems in motion, with a view to triggering new narratives and meanings as a result of that amalgamation of disparate elements. This collage impulse towards juxtaposition and hybridisation is quintessentially postmodern and, in Eno’s case, it dramatises one of the perceived pitfalls of postmodernism: a privileging of surface over historical engagement and depth, a lack of attention to history.

There’s been little sustained analysis of this potential weakness in Eno’s work, as most of his critics satisfy themselves simply by labelling him a dilettante. Sheppard touches on this with reference to Jon Pareles’s 1981 Billboard review of My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, one of the few contemporaneous responses suggesting a direction that more substantive critiques might take. On that album, Eno and Byrne sought to catalyse new musical narratives with their cutting and pasting of found and sampled sounds, but Pareles saw an ethical problem in what he deemed the album’s tendency towards dehistoricisation and cultural tourism. In his opinion, the excision and appropriation of elements of African and Middle Eastern traditions from their original context via samples was an instance of orientalist fetishism that “raises stubborn questions about context, manipulation and cultural imperialism.” This connects with the views of Eno associate Russell Mills (as quoted by Sheppard) regarding Eno’s visual artworks. Mills is less engaged by the visual works because of what he considers their hermetic nature as self-contained systems principally about themselves and their own processes; Mills feels that, rather than gesture outwards or exist in relationship to history, they’re cut off from material conditions, gesturing ultimately only to themselves. Indeed, Eno himself has spoken of the function of art exactly as a kind of escapism, as a flight from reality, but one that might, in turn, inspire improvements to reality.

My Life in the Bush of Ghosts and Talking Heads’ Remain in Light were the culmination of Eno’s fascination with African percussion and African music in general, forms that – ironically – appealed to him precisely because of their dynamic, radical relationship with their site of production. What made African drumming especially attractive to Eno was that it embodied and enabled non-hierarchical structures. Western traditions of the orchestra and the ensemble reproduced rigid social hierarchies in terms of both their organisation and the way they constructed music, starting with the authority of the composer and the notated score; African music, on the other hand, excited Eno because it relied on a more democratic “network” model of collaboration and improvisation. For him, this also resonated with the lessons on process and group-play learned from Ascott; with the possibilities for indeterminate music mapped by Cage and put into practice by Cardew’s cooperative Scratch Orchestra experiments; and with the theories of organisation, management and performance developed by Anthony Stafford Beer, whose books had interested Eno since the mid-’70s. Nevertheless, despite the attractiveness of a non-hierarchical model and the displacement of the authorial figure in favour of team work and mutual participation, a clear hierarchy reconstituted itself in the case of Remain in Light as the band fractured into opposing camps and the songwriting credits identified Eno and Byrne as the record’s principle composers.

In addition to its portrayal of Eno’s creative and intellectual life before Roxy Music, On Some Faraway Beach’s strongest segments are its coverage of his work with Talking Heads and Byrne; its dissections of his ’70s solo albums; and its discussion of the Bowie, Cluster and Robert Fripp collaborations. In fact, Sheppard devotes more than three-quarters of the book to Eno’s pre-1982 life and work, shoehorning the next 26 years into the remaining quarter (the ’90s are polished off in about 30 pages). This perhaps highlights a fundamental problem facing a biographer working on an artist with a lengthy and continuing career: that we don’t yet enjoy enough historical objectivity to evaluate fully the artist’s oeuvre, its context and its significance. However, Sheppard is clear on the reasons for the book’s biases, noting that “the last decade […] has offered little to truly match the luminous originality of [Eno’s] benchmark 1970s solo albums.”

That’s not to say that On Some Faraway Beach isn’t meticulously researched and hugely readable, balanced perfectly between contextualisation, commentary, astute analysis and fascinating anecdote. Sheppard also manages to squeeze in plenty of minutiae and amusing detail: the presence of a garden shed inside Eno’s Notting Hill studio; the fact that we have him to thank for inspiring Phil Collins to launch a solo career; eyewitness reports of Eno’s prodigious accomplishments with what Fripp once dubbed the “sword of union”; and (undocumented) claims by Eno that, in order to make ends meet, he briefly appeared in porn films.

Above all, the book skilfully blends Sheppard’s voice with the voices of his many compelling witnesses. Figures like Russell Mills and John Foxx, who have worked closely with Eno in different contexts, offer thoughtful, insightful observations. (Curiously, space is also given to less informative subjects with no first-hand working experience.) For the most part, it’s only the notion of Eno’s dilettantism that prompts less than favourable assessments by some interviewees. Even so, it’s interesting that despite suggestions that Eno and his work are all about surface and despite backhanded compliments about his ability to be persuasive on any topic, detractors don’t explain how this is the case or show they’ve explored the areas that Eno’s supposedly bullshitting about. Their criticisms also remain on the surface of things, rather than examine the conceptual framework underlying his wide-ranging work. (Wilson Neate)

(Originally published in Blurt magazine 2009)

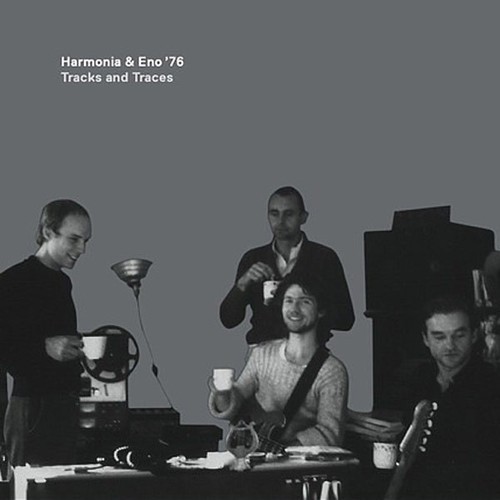

Harmonia & Eno ’76

Tracks and Traces

(Grönland)

In September 1976, Brian Eno knocked at the door of Harmonia’s studio in Forst. He was rather late. Two years had elapsed since he’d agreed to collaborate with Hans-Joachim Roedelius, Michael Rother and Dieter Moebius, and by the time he arrived (in the interim having publicly lauded them as “the world’s most important rock group”), Harmonia had actually split up. Notwithstanding Eno’s enthusiasm, their two albums had met with critical indifference and commercial disaster, and the band-members had already moved on to individual projects. Nevertheless, they spent ten or so days with Eno, experimenting and committing the results to tape. Plans to reconvene later didn’t work out, but a document of their brief encounter was released in 1997 as Tracks and Traces – an album put together by Roedelius, who, two decades after the fact, had unearthed one of the tapes made at the session.

The present re-release came about when Michael Rother found another tape, one containing Harmonia/Eno material that Roedelius hadn’t used for the first version of the album. Convinced of the newly discovered music’s strength, Rother set about incorporating it in a way that departed from the standard reissue modus operandi of simply adding “bonus tracks” as non-essential extras that are clearly separate from the original work. Rother elected to place two new pieces at the beginning and another at the end of the existing track sequence, establishing a frame of sorts: instead of intruding on and disrupting the album’s already complete musical picture, his frame preserves it intact; but crucially, the new frame also changes the listener’s experience.

Some might disagree with artists revisiting and revising their work after so long. It could be argued, though, that Roedelius’s 1997 version of Tracks and Traces was never the definitive, finished article since it was compiled by him alone: without consulting the others and without their creative input, he selected the materials, mixed them and decided the order of the tracks. In that sense, Rother’s return to the album is entirely legitimate, while it also accentuates the potential of any work as a work-in-progress, open to remaking and remodeling. And as it turns out, Rother’s inventive reimagining of Tracks and Traces is, in fact, a welcome one. It wasn’t that the quality of the material assembled by Roedelius was deficient; rather, his presentation of that material felt somewhat uneven, the track sequence vaguely unsatisfying. By reframing the work, Rother highlights that unevenness but also, more importantly, remedies it.

Roedelius’s Tracks and Traces began with a sonic journey already underway, the bright, jittery locomotive chug of “Vamos Compañeros” eventually depositing listeners in the album’s darker, more abstract heartland: the core suite of “By the Riverside,” “Luneburg Heath,” “Sometimes in Autumn” and “Weird Dream.” On Rother’s reframed version, listeners are now greeted by “Welcome,” a tranquil, beatless salutation threaded with simple melodic guitar lines; then, on “Atmosphere,” shuffling beats, subtle drones and shimmering melodies set things in motion, forming a seamless segue into the driving, rhythmic pulse of Roedelius’s 1997 opener. These new tracks establish a well-paced build, which, in turn, softens the sudden mood change after “Vamos Compañeros,” as listeners encounter the record’s quieter, contemplative interior. Here, pastoral-industrial soundscapes conjure up natural environments in keeping with their titles: for instance, the organic and metallic “By the Riverside” blends faint birdcalls with Rother’s harsh, processed guitar textures; throughout the eerie “Luneburg Heath,” a spooky Eno wanders in and out of the drifting synthesized mist, counseling, “Don’t get lost on Luneburg Heath.”

Just as the new opening pieces evoke the start of a voyage, which then unfolds over the course of the record, the new final track, “Aubade,” suggests the completion of a journey, with an arrival or perhaps a cyclical sense of return. While, originally, the record’s austere middle passage began to yield with the melodic idyll, “Almost,” and the slide-guitar infused carousel ride of “Les Demoiselles,” that progression was ultimately undermined: the closing sketch, “Trace,” sounded incomplete, finishing the album on an open-ended, unfulfilling note that also reprised the darker, more restive tone. Now, “Aubade” offers a more satisfying, restful conclusion and gives the album a greater feeling of unity and symmetry. As its title’s allusion to the medieval literary tradition of the dawn song implies, the track itself consummates the passage from the record’s darker interior into the light, with Rother’s bittersweet valedictory guitar bringing things full circle and emphasizing closure.

Although a potentially risky endeavor, Rother’s reimagining of Tracks and Traces is wholly successful. Without intervening directly in the structure of the existing work but by instead reframing that work, he offers listeners a fresh appreciation of it and a far more rewarding aural experience. (Wilson Neate)

(Interview from 2009)

After Portishead’s second album, Geoff Barrow quit music for five years. Since the 2008 release of Third, though, he’s remained active, as boss of the Invada label, as a producer (The Horrors’ Primary Colours) and now as a member of BEAK>, a Bristol trio featuring Billy Fuller (Fuzz Against Junk) and Matt Williams (Team Brick).

Whereas nearly eleven years passed between the second and third Portishead albums, BEAK> hatched their debut in just twelve days. An exercise in what Barrow calls “instantaneous writing,” this is a Krautrock-influenced affair, infused with a touch of proggy weirdness, some drones and out-there noise and a bit of doom-metal heft. Although BEAK> shares a few influences with Portishead’s last album, particularly an affinity for Simeon Coxe’s Silver Apples, Barrow also sees BEAK> and Portishead as worlds apart. Exploring a largely different creative process, traveling to gigs on budget airlines, carrying his own gear and playing small venues all add up to a welcome change, one that he finds re-energizing.

Barrow spoke to BLURT about working with BEAK> and, among other things, his love of Can, his ambivalent relationship with Bristol and the difficulties posed by being a singing drummer.

BLURT: As an expat Bristolian, I was immediately struck by the track titles on the BEAK> album, many of which are the names of places around Bristol. Is that just playful or is there a link to the music?

GEOFF BARROW: It was very playful but, at the same time, we kind of said, “No, no that doesn’t sound like [the village,] Pill – that one sounds like Barrow Gurney.” So there was a connection, but it was definitely a playful connection. But when I think of the place, Pill, I do think of that tune [“Pill”], and when I think of Barrow Gurney, I do think of that tune, cos it’s a sort of mad synthesizer tune.

Yeah, the sound is pretty manic – so the title “Barrow Gurney” refers to the Barrow Gurney psychiatric hospital, rather than the village of Barrow Gurney itself? When my grandfather was frustrated with us he used to say, “You’ll drive me out Barrow Gurney, you will.”

Yeah, right. I know a lot of people who went to Barrow Gurney and a few mates of mine worked there as well, as mental health nurses. It’s closed now. It’s all Care in the Community now. They all do crack…. That was Thatcher for you.

And is “The Cornubia” a reference to the Cornubia pub in Bristol?

Yeah, it’s a proper Real Ale pub…. As I was saying that, I felt like a proper Real Ale drinker [laughs]. We had an Invada night at the Cornubia and we got banned from putting on gigs there again. It’s a good pub. It’s one of the only real pubs left standing in Bristol. I think it actually survived the bombing in the [Second World] War. If you see pictures of it, it literally stands alone. It’s the most peculiar kind of setting because everything else was destroyed either side of it, in front of it and behind it, and it just stood.

Bristol was bombed heavily in the Blitz. My mum’s house actually took a direct hit, killing most of her family.

Bloody hell! Bristol got hit badly during the War. If you look at photos of how it was before the War and afterwards, you can really see it. It’s pretty different.

A lot of Bristol musicians have stayed in the area. Do you feel a strong connection to the West Country?

I don’t know really. I just haven’t really been anywhere else. It’s home. At times I don’t like Bristolians and I don’t like what the city’s become. I don’t really like the history of the city, either, but this is where I live.

When you mention the history, are you referring to the slave trade in particular? [In the 18th century, Bristol prospered as a key British port in the triangular trade.]

Yeah, and the corruption. It’s always been corrupt. Do you know that book, A Darker History of Bristol by Derek Robinson? It’s a thin book that takes you on a little historical trip into why Bristolians are the way they are. They’re pretty apathetic. They don’t really want to join any side. They just want to get pissed and have an all right time, really. It’s got that kind of port mentality, you know? Like Liverpool. It’s got that about it. People just can’t be bothered down here, really. The only people who can be bothered are thieves and mercenaries.

You recently organized a big event at the Colston Hall in Bristol featuring bands on your Invada label. There’s been controversy surrounding that venue because it’s named after the Bristol merchant Edward Colston, a prominent figure in the slave trade. Do you think the name will actually get changed or do people not give a shit?

Bristolians don’t give a shit about it, but the middle classes do. So it will change its name eventually because it’s like having a place called the Hitler Rooms. It doesn’t sound great, does it? Or the Goebbels Village Hall.

It doesn’t really have a good ring to it.

Maybe the Goebbels Community Center? I think it’s got to change and eventually it’ll just happen. It’s just a name, but you’ve got to move forward. So yeah, we did the Invada Invasion there. We took the place over with Mogwai and a load of other bands. It was a really good night for people into alternative music. That’s something that just doesn’t happen in Bristol, and we just thought, “Right, we’ll do it.”

Was BEAK> a collaboration that had been on the cards for some time?

I think we’d all always liked what each other did. I’ve always liked Billy and his bass playing and stuff, and I’ve always been a fan of Matt’s. I mean, that’s the reason I put out their records on Invada. And we played together at a New Year’s Eve party, and me and Billy said it’d be great to do it again – and that was two years ago. Then we bumped into each other and said it again. And Matt (as Team Brick) had played on the last Portishead record and we had this bit of free time, so we did it. But there was no discussion about it, really. We just went in there and set up the microphones, and the first thing we played was basically the first track on the record, “Backwell.” As you hear it, it’s pretty much the first time we played together, which was really refreshing.

So was the record largely put together from improvisation and, for want of a better word, jamming?

It all came about in that way, although I’m not really into the term “jamming” – it was more about a kind of instantaneous writing, really. Cos jamming, to me, reminds me of bands that stick on a chord and play a solo for a couple of days, do you know what I mean? Like the saxophone player goes [approximates ostentatious jazzy sax solo] and it’s all about getting your chops in, and it’s just bollocks. For me, it was about being sat there and being aware of the space you’re in and the sound you’re creating: being totally aware of it and then moving things forward and just trying to write instantaneously. It was like a flow of consciousness, really – whether it’s lyrics or melodies or whatever. We actually played things a couple of times when we said, “Yeah, that’s a really good idea, but it completely went and fucked up there. Shall we just have another go at it?” And it wouldn’t be a couple of days later, it would be in the same half an hour. But in the end we’d usually go back to the first take and say, “Oh, it had something about it.” So, like I said, there wasn’t really that much discussion. We’d listen to a track after we’d played it and it’d be like, “Well, that’s done!” And there wasn’t a sense of it being throwaway, it was more like it just being refreshing. I mean, the album’s got bits that fuck up on it, but that’s what gives it its character – rather than it being put on Pro Tools and some bloke moving the snare drum so it’s in time. It’s not that kind of music, you know.

Do you think the experience of the way you work with BEAK> will feed back into how you do things with Portishead?

Well, the thing is that Portishead has actually always had that aspect of it. Like the song “Numb” on Dummy – it was written by me being sat in one room with a sampler and Ade [Adrian Utley], Gary [Baldwin] and Clive [Deamer] basically doing the same thing that BEAK> does. But that came from a hip-hop loop mentality. So it would be like, “Yeah, play that again,” and I’d just stick it in the sampler and loop it up. So Portishead have always had that, really. It’s just that people get a different impression because we’ve taken so long over records. Because of that, people perceive that it’s a more traditional setup. Portishead is weird – it can be instantaneous. Like sometimes the riff is written in an afternoon, but the beat takes twelve months. It’s just kind of fucked. And anything that can help my brain to be more productive in a writing way is great, but you can’t leave one record, do nothing and then start a new record without feeding your brain. That’s why I gave up music for five years, really, after the second Portishead tour, because I was kind of empty of ideas. I didn’t want to prove anything, didn’t want to move forward.

In addition to improvising the music, you also made up the lyrics as you recorded the BEAK> tracks. When you play live, do you invent new ones?

Yeah, basically, there’s a general vibe with the lyrics; there’s always one word that fits in it – like the sound of the pronunciation, how it suits the mood – and then you just kind of make it up. It’s interesting because playing drums and singing, it’s odd anyway.

You’re now part of a great tradition of singing drummers: Robert Wyatt, This Heat’s Charles Hayward, er, Karen Carpenter…. Is it difficult?

Yeah, it’s pretty mad, singing drummers [laughs]. You know, I’ve never done it before. It’s not too bad. It can throw you a bit. Thinking about the lyrics at the same time as you’re playing, it’s like tapping your head and rubbing your tummy at the same time or playing keepie-uppie with a football.

You’ve said that you don’t really enjoy playing live with Portishead. Are you enjoying it more with BEAK>?

I am, yeah, to be honest. Recently we’ve been playing not gigs, but little places – like we played a gallery the other day, without a PA. We’ve been playing most of the gigs like that, without a PA. We just set up and it’s refreshing; there’s no real pressure. There’s a huge difference between that and playing Coachella, you know what I mean? I engineer the drum sound when Portishead play live and me and Ade are like the MDs of it. And with BEAK> it’s a very simple kind of setup: playing live is pretty much as we recorded the album. There’s a couple of echo boxes we use to get that kind of dark, deep reverb sound, and it works and I’m not stressing over it. So, yeah, it has been really enjoyable. I mean, setting up your own kit and setting up your own sound and all that kind of stuff has been quite funny as well. When you compare touring with Portishead, with a crew of eighteen, to BEAK> on an easyJet flight with a synth in a suitcase and a snare drum in your pants, then basically it’s a different vibe. But it’s all really refreshing and gives you a different take on things.

So doing BEAK> has been re-energizing for you, musically?

Yeah, it has been. I think Ade finds it incredibly refreshing to play with other people. And Beth [Gibbons], as she’s writing her songs, it comes from a different part anyway – so it’s all good for feeding us. Our brains being fed like that was what brought the last Portishead record about.

Some of the influences I heard on the BEAK> album were, maybe, “Church of Anthrax,” Tony Conrad and Faust, Silver Apples, Can. Are these things you’ve all been listening to?

What was that first one?

“Church of Anthrax,” a track by Terry Riley and John Cale, from 1971 – very much in a Krautrock vein….

I don’t know it, but it sounds great! [laughs] We’re definitely into lots and lots of different music, especially the Can thing. I think we’re definitely influenced by them. I think they’re an incredible band, and if we’ve got anywhere near to where they were…that’s just brilliant. We didn’t try to sound like them, though. It’s just where I’ve found myself rhythmically, coming out of being influenced by hip hop and electronic music and having a vibe where it’s got a beat and it’s heavy, but heavy in the right way – it’s not heavy sonically, like, “I’m gonna smash your head in with this sound.” Our influences are pretty wide, especially what Billy and Matt are into. Matt’s really into the Cardiacs and Billy’s really into bands like Plastic People of the Universe, and I’m into that as well: music that’s really out there, but that still retains melody and rhythm. I really like Moondog, too – that was a big influence on the last Portishead record.

And Silver Apples….

Yeah, yeah – I’m actually interviewing Simeon for a magazine. We met at All Tomorrow’s Parties and it was really weird because he was playing in Bristol and he asked me to play the drums, but I didn’t do it. If it was now, I would have done it, but back then I hadn’t played drums in quite a long time. So maybe we’ll just arrange it again. Maybe I’ll see if he wants to play again. But yeah, our influences are there. We’re not embarrassed by them. We think they’re brilliant bands.

Some musicians I’ve interviewed emphasize that they don’t listen to any other music, so as to avoid being influenced. That’s not the case with you, then?

Well, it’s really strange because I actually listen to very, very little music. An incredibly small amount. Like I’ll get into a Silver Apples track or one Can album, Ege Bamyasi, and I don’t want to hear any more. I just want to hear that one. I think it’s just a perfect record. It’s weird: I’ve always made more music than I’ve ever listened to. I don’t know much about other artists and I don’t know about their techniques or anything – I’d like to! – but Ade’s kind of the opposite. He’s a walking encyclopedia of music, but I just like to make music, really. And he does as well, of course. Ege Bamyasi is an absolutely genius record. I first heard Can on [BBC] Radio 1. It was Mark E. Smith on Radio 1 talking about his favorite tracks. It was around 1990 or something, when I was listening to A Tribe Called Quest and Gang Starr and stuff like that. And Can’s “Vitamin C” came on and I was bowled over. It was just like the first time I ever heard Public Enemy as a kid. I thought Can were a new band, and I thought they were the greatest band that ever lived [laughs]. I still think that tune is just unbelievable. No one’s even gone close to it, really.

Talking of Can, did you see that recent BBC documentary, Krautrock: The Rebirth of Germany?

Yeah! What I absolutely loved about everybody in it was their true feeling that they were just doing it because they were doing it – for no financial gain or anything else. They were just really solid in their musical form, and they were still there. Which is a really lovely thing.

[Originally published in Blurt magazine, 2009]

It’s hard to overstate the importance of the ‘70s generation of experimentally minded German musicians like NEU!, Kraftwerk, Harmonia, Can and Faust, usually grouped under the dodgy term, Krautrock. Having come of age in the postwar period, many of these diverse artists shared a common bond of refusal, rejecting not only their country’s troubled political and cultural past, but also the global hegemony of Anglo-American pop and rock. Ironically, despite distancing themselves from the musical mainstream, these bands would exert considerable sway over those traditions they’d rejected. The line of influence stretches from punk’s smarter manifestations through the post-punk generation and Bowie’s vital late-’70s work, to more recent rock of all stripes – Sonic Youth, Tortoise, Stereolab, Radiohead, Primal Scream, Secret Machines, the list goes on and on. And beyond rock, the likes of Cluster, NEU!, Kraftwerk and Harmonia have also been perennial reference points on the continuum of electronic music from the late ’70s to the present, from synth-pop to techno, as well as its more abstract, experimental variants.

Michael Rother’s guitar minimalism is a connecting thread weaving through and between several of the most innovative of the ’70s German bands. When Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider briefly separated in 1971, Rother joined Schneider in Kraftwerk. Also present, on drums, was the late Klaus Dinger, with whom Rother formed NEU! later the same year. Between NEU!’s second and third records, in 1973, Rother teamed up with Cluster’s Dieter Moebius and Hans-Joachim Roedelius as Harmonia, a project spawning two studio albums, Muzik von Harmonia and Deluxe, plus two posthumous releases: Live 1974 and a collaboration with Brian Eno, Tracks & Traces. By 1977, Rother had hooked up with Can’s drummer Jaki Liebezeit and embarked on a solo career that continues today.

Despite solo success, particularly with his first three records, Rother is still most widely known for his work with Dinger in NEU! Immensely creative as an artistic unit, Rother and Dinger were never friends, and by the mid-’90s, with the band long dead and its three original albums out of print, the pair’s relationship had been reduced to an exchange of fraught faxes after Dinger – without Rother’s approval – began putting out unreleased NEU! material on a Japanese label. Thanks to Dinger’s intransigence, the original NEU! albums remained legally unavailable until 2001, when Herbert Grönemeyer stepped in and brokered their release on his Grönland label, which later also issued Harmonia’s archival Live 1974. The latter prompted renewed interest in Rother’s recordings with Roedelius and Moebius, which in turn led to the reactivation of Harmonia for live performances from 2007 through early 2009.

Now, on the occasion of Grönland’s expanded reissue of Harmonia and Eno’s Tracks & Traces, Michael Rother looks back over a career of sometimes vexed but always groundbreaking creative partnerships.

How did you first connect with Hans-Joachim Roedelius and Dieter Moebius? Did you know them personally or just through their work as Cluster?

We did a concert together, in Hamburg, when I was with Kraftwerk in ’71. Cluster worked with the same producer – Conny Plank – and I’m not sure how it happened, but we ended up playing at the same concert in Hamburg.

So both bands were on the same bill?

Yes, they were playing on the same night: it was Kraftwerk and Cluster in the big university hall there. There’s a funny story about that. I’ll never forget that concert. Kraftwerk were quite popular already. The first Kraftwerk album had been released some months earlier and so, obviously, for the crowd, we were the main attraction, but we were so democratic [laughs] that we talked to Roedelius and Moebius backstage and asked, “Who should go on first?” And they said, “Oh, you go on first and then we’ll take over.” There are hardly any documents of what we did as Kraftwerk, but we’d really been making quite rough music and people were very excited and when we wanted to stop our set, the people just kept on cheering and shouting and we said, “No, we have to stop because the other band’s coming on.” And then, when Cluster started playing, the people got really mad and they rushed the stage. I don’t know how many, but maybe 20 or 30 people actually went onto the stage and disconnected their speakers and equipment. I was afraid they would start beating them up. That was the result of Kraftwerk’s furious playing!

These days people don’t tend to think of Kraftwerk as a rock band whipping crowds into a frenzy!

Cluster played very soft music, but what we did as Kraftwerk then wasn’t very soft. It was quite the opposite: it was very rhythmical, very rough, primitive, raw music. Well, that was my memory, at least. Maybe they weren’t really in danger of being beaten up, but it’s something I’ll never forget. So anyway, after that we stayed in touch and one year later, when we had already released our first NEU! album, we had this offer to do a tour in the UK. Our British label, United Artists, invited us and of course the two of us, Klaus Dinger and I, couldn’t perform live – playing just drums and one guitar, that’s not enough. And then I remembered especially this one track on Cluster II, “Im Süden.” That track really appealed to me and I had the idea that the harmonious, melodious connection was there. So I went to visit Cluster in Forst and jammed with Roedelius in order to find out whether they could join NEU! on that tour, as members of the live line-up. But, actually, in the end I liked that music much more than NEU! so [in 1973] I stopped NEU! for a while.

What was it about Cluster that you found so attractive – attractive enough to put NEU! on hold?

When we jammed together it was a different world, a different atmospheric world. It was quiet. Roedelius played these melodious patterns on his keyboard – I think there was maybe some influence from minimalist composers – and there was the sound treatment, of course. Sometimes it was fuzzy – he used wah and other filters. It was very primitive gear, actually. Nothing sophisticated. In fact, it was very similar to what I had been using with NEU! but the combination of Roedelius’s piano, his electric piano, and my guitar was immediately something that connected. And, well, there was so much to discover on that road.

You mentioned minimalism. Had you listened to composers like Terry Riley by then?

Not by that time. Until then, I hadn’t come in contact with any of them. It was only really when I met Roedelius and Moebius.

How did working with them as Harmonia compare to working with Klaus Dinger in NEU!?

Well, there were several differences. One big difference was that with Cluster as Harmonia we could create music onstage: it was a complete musical picture. That was totally different to NEU! With Klaus, we needed the multitrack machine and that limited our possibilities, of course. And also, to be honest, I respected Klaus as an artist, as a great drummer, but as I’m sure you’ll have heard, we were so different in character and personality. Maybe sometimes the impression that’s created is wrong, but we weren’t friends. I didn’t want to spend any time with Klaus outside the studio. In the studio, it was perfect. We were a great team. We didn’t have to discuss music in the studio because we had similar visions of where we were heading and what we wanted to do. But everything else was not so pleasant for me with Klaus. With Moebius and Roedelius, it was different. Klaus thought of himself as a hippie – in later days he referred to himself as a hippie-punk or something like that – but the calmness and surroundings of Forst had a strong appeal to me, and this all connected. It was just one big excitement. The visit to Forst was inspiring; it was an inspiring place for me to stay.

As you say, you and Klaus had very different personalities and you weren’t friends. How did you come together initially?

I met him when I stumbled into the Kraftwerk studio in Düsseldorf one day, in early ’71. At that time, I was working in a psychiatric hospital, as a conscientious objector [in lieu of compulsory military service], and I was with a friend who was also a guitar player and we were in Düsseldorf demonstrating against something or other – I can’t remember what it was [laughs]. At the time, there were so many reasons to be angry. Anyway, after the demonstration he said, “Oh, I have this invitation to go into the studio of a band here in Düsseldorf. They want to do some film music or something.” He told me the name of the band and that didn’t ring a bell – I hadn’t heard of the name Kraftwerk at the time. So, I joined him and I jammed with Ralf Hütter in that studio. Florian Schneider and Klaus Dinger were sitting on the sofa listening and, obviously, everyone had the same impression that there was something happening musically. I got on very well with Ralf Hütter. He was also a big surprise for me because there was no need for discussions: it was just the similarity of our music, our harmonious, melodious ideas maybe – something like that – as opposed to the blues-oriented rock musicians playing guitar solos that were around all the time in the late ’60s.

Although you’d originally been inspired by Anglo-American rock, you weren’t interested in reproducing it.

Well, I grew up imitating all those people. I mean, the last one who really knocked me off my feet was Jimi Hendrix and I still love his music. It’s still inspiring and it’s so amazing what he did at that time. But, of course, it was necessary to forget what I had heard and what I had been impressed by in the late ’60s in order to be able to move forward and create my own music. And when I met the Kraftwerk guys, that was suddenly a sort of…in English do you have the phrase Hour Zero?

Yes, or Zero Hour or maybe Year Zero if you’re talking about big socio-cultural paradigm shifts.

In German it’s a very common expression, Stunde Null. It’s used for postwar Germany, after the collapse of Nazi Germany. And everything started for me at that moment in ’71, with Kraftwerk. So my main idea was to forget the clichés, all the guitar techniques and song structures of my teenage heroes, which I had so carefully adopted and copied. The Beatles, Eric Clapton and Hendrix were already around, I understood that, and copying their ideas would never be an expression of my own musical personality. The first thing I did was to slow down my fingers: no more running around on the guitar neck at high speed. Then, consequently, the ideas of pop music and blues – their melodic and harmonic song structures – were scrapped from my musical vocabulary. All of this left me with the basic elements of music. One string, one idea, move straight ahead, explore dynamics. An echo of my listening to music in Pakistan, probably [where Rother lived as a child]. Anyway, this minimalistic approach was not limited to guitar playing. It was an idea for a complete music which – in the end – was meant to express and reflect my own personality and individuality. It probably sounds very ambitious and self-confident – but that’s what I was, what we were. The future wasn’t clear, I didn’t know in 1971 where the musical adventure was taking me, but it was a vast open ground with lots of freedom and the chance of limitless experimentation.

So when you were working with Kraftwerk and then NEU!, you consciously tried to cut yourself off from the rock tradition.

Yes, completely. You know, it wasn’t enough just to forget the English and American musical heroes. German also…. Actually, there were really no German musical heroes that I can remember – whatever I heard from German musicians was something that didn’t impress me. Later on, when I played with Kraftwerk, we also met the Can people. We had, I think, one or two concerts together and, of course, later on I listened to their albums – not closely, but enough to know that Jaki Liebezeit was a great drummer. And that, of course, led to our collaboration later.

And you only felt musical kinship with people like Can, Kraftwerk and, of course, Cluster?

Yes. Maybe that’s some sort of a family, but with very loose ties. I chose to be influenced and inspired by the people I collaborated with and not, you know, by just anyone who put out a record.

By the time you joined Kraftwerk, they’d already released that first album.

Yes, that’s right. It was a few months earlier and they were becoming popular. I remember there was talk about the “Heroin Crowd” in Munich being totally taken by this first album, and then, when we did our concerts, our tours, there were so many people, especially young people, who discovered the music and it took off like a rocket.

Is there any chance that the work you did with Kraftwerk will be officially released? Some of the aborted studio work with Conny Plank or the live material?

It’s hard to say. I hesitate to say never because many things happen that in earlier times I wouldn’t have considered possible. I mean, the lost Harmonia tapes with Brian Eno, for instance – the Tracks & Traces tapes. But I know, of course, that Florian Schneider and Ralf Hütter did their best to forget the period in ’71 when they were separated. They tried to erase that part of their history, even saying that the actual Kraftwerk story starts with Autobahn in ’74, which is quite ridiculous.

They certainly did some interesting work before Autobahn.

Yes, and some of the best work, in fact. Of course, I haven’t discussed that with them; I haven’t spoken with them for ages. Now I hear that they’ve split. I met Karl Bartos recently, who was with them for a long time, and he tells me it’s only Ralf Hütter now. But as for the recordings we did with Conny Plank, to be honest, they weren’t great. That was one of the reasons we stopped halfway through, because, well, maybe it wasn’t the right combination. When we did it live, sometimes in the right situation, the music got very, very exciting – for us onstage and also for the crowd. I think that the videotapes and the bootlegs that are available do not reflect that. Some of them are completely wrong in the audio balance. I think the reason for this is that the technicians didn’t realize how important the stuff was that Florian Schneider played. Instead, they concentrated on my guitar much too strongly, making it dominate everything. And I thought that Florian did amazing things on the electric flute, especially. If there would be a possibility to remix that, to do proper audio balance, I guess it would be much more exciting than what is available, but I don’t see Florian or Ralf Hütter at a certain time suddenly approaching me and saying, “Hey this has to be released!” [laughs]

You’re not in touch with Florian Schneider at all these days?

No. I have friends who sometimes see Florian. I don’t know, maybe I’ll meet up with him one day. He seems to be getting calmer since he left Kraftwerk. But no, there was no reason to stay in touch. I mean, we weren’t friends either. The music was exciting, but I also remember being witness to some horrible fights between Klaus and Florian: horrible arguing…and really crazy driving! Florian was such a crazy driver. I think he risked our necks many times because he was so on-edge. Everything was the complete opposite of being relaxed and driving with foresight. He didn’t drive carefully…or maybe that was just my impression because I didn’t have a driver’s license at the time. But I think it was quite true because that’s how Florian always appeared to me anyway.

Let me ask you about the dreaded term Krautrock. This was a term invented by the British music press, I think.

I can’t say. It could well be, but there are several versions of the origin of this word. You know the band Faust? I heard they had a song called “Krautrock,” but I don’t know their music.

You’ve never listened to Faust?

Not really. Well, actually someone once gave me a record [laughs], but [listening to other people’s records] isn’t so important, really. I mean, I have my own job to do!

That’s funny. Although it’s heavier, Faust’s “Krautrock” sounds vaguely similar to the kind of thing you were doing earlier with NEU! on “Hallogallo.”

Hmmm, maybe I should go and listen to Faust.

Did you find the term Krautrock at all offensive? Or was it amusing?