(Originally published in Blurt magazine 2009)

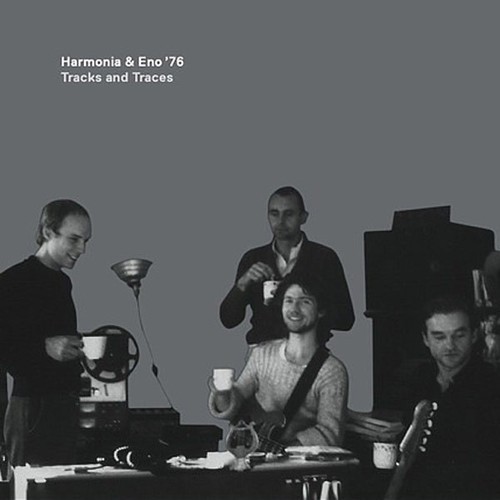

Harmonia & Eno ’76

Tracks and Traces

(Grönland)

In September 1976, Brian Eno knocked at the door of Harmonia’s studio in Forst. He was rather late. Two years had elapsed since he’d agreed to collaborate with Hans-Joachim Roedelius, Michael Rother and Dieter Moebius, and by the time he arrived (in the interim having publicly lauded them as “the world’s most important rock group”), Harmonia had actually split up. Notwithstanding Eno’s enthusiasm, their two albums had met with critical indifference and commercial disaster, and the band-members had already moved on to individual projects. Nevertheless, they spent ten or so days with Eno, experimenting and committing the results to tape. Plans to reconvene later didn’t work out, but a document of their brief encounter was released in 1997 as Tracks and Traces – an album put together by Roedelius, who, two decades after the fact, had unearthed one of the tapes made at the session.

The present re-release came about when Michael Rother found another tape, one containing Harmonia/Eno material that Roedelius hadn’t used for the first version of the album. Convinced of the newly discovered music’s strength, Rother set about incorporating it in a way that departed from the standard reissue modus operandi of simply adding “bonus tracks” as non-essential extras that are clearly separate from the original work. Rother elected to place two new pieces at the beginning and another at the end of the existing track sequence, establishing a frame of sorts: instead of intruding on and disrupting the album’s already complete musical picture, his frame preserves it intact; but crucially, the new frame also changes the listener’s experience.

Some might disagree with artists revisiting and revising their work after so long. It could be argued, though, that Roedelius’s 1997 version of Tracks and Traces was never the definitive, finished article since it was compiled by him alone: without consulting the others and without their creative input, he selected the materials, mixed them and decided the order of the tracks. In that sense, Rother’s return to the album is entirely legitimate, while it also accentuates the potential of any work as a work-in-progress, open to remaking and remodeling. And as it turns out, Rother’s inventive reimagining of Tracks and Traces is, in fact, a welcome one. It wasn’t that the quality of the material assembled by Roedelius was deficient; rather, his presentation of that material felt somewhat uneven, the track sequence vaguely unsatisfying. By reframing the work, Rother highlights that unevenness but also, more importantly, remedies it.

Roedelius’s Tracks and Traces began with a sonic journey already underway, the bright, jittery locomotive chug of “Vamos Compañeros” eventually depositing listeners in the album’s darker, more abstract heartland: the core suite of “By the Riverside,” “Luneburg Heath,” “Sometimes in Autumn” and “Weird Dream.” On Rother’s reframed version, listeners are now greeted by “Welcome,” a tranquil, beatless salutation threaded with simple melodic guitar lines; then, on “Atmosphere,” shuffling beats, subtle drones and shimmering melodies set things in motion, forming a seamless segue into the driving, rhythmic pulse of Roedelius’s 1997 opener. These new tracks establish a well-paced build, which, in turn, softens the sudden mood change after “Vamos Compañeros,” as listeners encounter the record’s quieter, contemplative interior. Here, pastoral-industrial soundscapes conjure up natural environments in keeping with their titles: for instance, the organic and metallic “By the Riverside” blends faint birdcalls with Rother’s harsh, processed guitar textures; throughout the eerie “Luneburg Heath,” a spooky Eno wanders in and out of the drifting synthesized mist, counseling, “Don’t get lost on Luneburg Heath.”

Just as the new opening pieces evoke the start of a voyage, which then unfolds over the course of the record, the new final track, “Aubade,” suggests the completion of a journey, with an arrival or perhaps a cyclical sense of return. While, originally, the record’s austere middle passage began to yield with the melodic idyll, “Almost,” and the slide-guitar infused carousel ride of “Les Demoiselles,” that progression was ultimately undermined: the closing sketch, “Trace,” sounded incomplete, finishing the album on an open-ended, unfulfilling note that also reprised the darker, more restive tone. Now, “Aubade” offers a more satisfying, restful conclusion and gives the album a greater feeling of unity and symmetry. As its title’s allusion to the medieval literary tradition of the dawn song implies, the track itself consummates the passage from the record’s darker interior into the light, with Rother’s bittersweet valedictory guitar bringing things full circle and emphasizing closure.

Although a potentially risky endeavor, Rother’s reimagining of Tracks and Traces is wholly successful. Without intervening directly in the structure of the existing work but by instead reframing that work, he offers listeners a fresh appreciation of it and a far more rewarding aural experience. (Wilson Neate)