[Interview originally published in Blurt magazine, 2010]

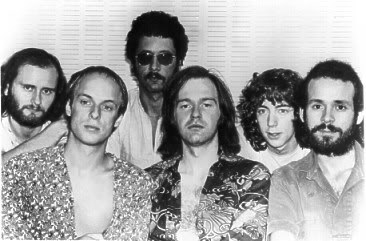

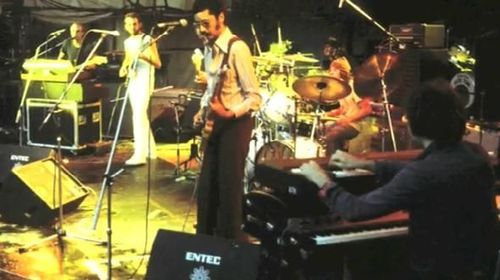

In the scorching British summer of 1976, with Roxy Music on vacation and with punk about to explode, Roxy guitarist Phil Manzanera and friends convened the art-rock supergroup 801. Featuring several rather musicianly musicians and one avowed non-musician – speaking mutually incomprehensible languages – this incarnation of the band was a short-lived, precarious alliance. However, the seeming irreconcilability of 801’s constitutive elements was a source of uniquely creative tension throughout its fleeting, six-week existence. During that time, the band played just three gigs, the last of which was preserved on the 801 Live album, recorded in September 1976 and originally released the following month. (Manzanera did continue the project in 1977, but not with this classic line-up.)

With Roxy Music, Manzanera played a key part in one of the most influential and iconic British groups of the ‘70s, but he’s always been especially proud of his work with 801. So much so that, with old bandmate and longtime associate Bill MacCormick, he’s now assembled the definitive version of the only album by the original 801, bundled with a completist-pleasing booklet and a second CD that features a revealing recording of the group’s final dress rehearsal at Shepperton Studios.

Phil Manzanera fills Blurt in on the whys and wherefores of the band that was almost called Sponge and discloses the identity of Sid Vicious’s favorite Roxy musician.

When 801 got together in summer ’76, had Roxy actually disbanded or were you just on hiatus?

I think we’re always on hiatus [laughs]. I mean, right now, until about an hour ago, I was wondering how long a hiatus could last, but then I’ve just spoken to Bryan [Ferry] and we might be hatching a new plot. The whole story of Roxy is one of complete no-career-path-at-all: you know, people just seem to do what they feel like doing and pay no attention to building a long-term career – which is probably the correct thing to do. Which, I suppose, is why you become a rock musician, because you don’t care about a career, really. You just want to get on and do it, and you don’t think about that. So, at any given moment, Roxy are in flux and at that moment in ’76, I can’t remember which particular flux we were in. But we must have been in one.

What prompted you to reissue 801 Live at this point?

Well, it’s been a labor of love, really. I’ve been in love with this project for many years. Bill MacCormick, the bass player in 801 – who I’ve known since I was about 12 years old at school – helps run the web site and we’re like a little cottage industry. We’re always plotting and planning and scheming. The 801 project is something we’ve both always been very proud of and Bill suddenly realized he had this tape of the Shepperton rehearsal and then we started wondering if a friend of ours, who took photos, had any pictures that we hadn’t seen. So we tracked down this guy, who lives in Switzerland now, and he looked in his attic and he found these rolls of film. We had them printed and all of this new stuff appeared. So we thought, “Right, let’s give this a good send-off – once and for all!” [laughs]. And then I couldn’t help but just stick lots of other things in the booklet that accompanies the album. You know, it’s just one of those things you almost do for yourself, really. You get to a certain age and you start looking back and you say, “Oh that was nice!” And then you start dragging out pictures. It’s like looking in your family album.

The 801 project really captures a moment, in all different areas: in one’s youth, in each person…. It was literally a month or so before Eno went off to work with Bowie, for the rest of his life virtually [laughs]. It’s just before Simon Phillips became a famous drummer and everyone wanted to work with him, people like Jeff Beck, Mick Jagger – you name it. Francis Monkman, at the time, was just about to start doing all sorts of interesting new things, like Sky with John Williams. We just happened to catch these people for six weeks and made them rehearse. We hatched this plot, you see – me, Eno, Bill and Bill’s brother, Ian MacCormick, who’s now no longer with us, I’m afraid – in a cottage in Shropshire. Those six weeks won’t happen again, and it was just a miracle that a series of things led to it being recorded.

Was it always intended to be momentary? Was there no plan, at the time, to develop 801 and write original material after the live shows?

No, you couldn’t have kept that band together. In the booklet, I got everybody to write something about their experience, even if it’s virtually nothing. So Eno, Francis, Simon, me and Lloyd [Watson] have something, but Bill actually writes about 3500 words. He has diaries and everything. So people will be able to read there exactly what happened with 801 and why – which I couldn’t remember. Eno’s thing is, “I have virtually no recall of the ’70s. I don’t know what happened.” So it varies from that and gradually you get more and more until, finally, you get 3500 words from Bill, which I edited down because it had gone off into short story territory [laughs]. So it’s all there in the booklet in a lot of detail. It’s great for me to read it and see the what, why and how – what was going on and the context of it all.

You knew Bill, Eno and Lloyd Watson. How did the others come to be involved?

Bill brought Francis along, because they were going to form a band with Robert Wyatt. It was going to be a continuation of Matching Mole, the band Robert had before he had his accident. I think they may have even played together a bit. And I had met Simon when he was up at Air Studios and we were recording with Roxy. I’d heard him play. He was incredibly young. We were all totally equal shareholders in this and we wanted it to be a band thing. At the time, Simon was just doing sessions and he wanted a session fee, and I had to actually say to him, “No, you don’t understand, this is like a band” – because he had actually done sessions for Jesus Christ Superstar and, at the time, you could either take the money or percentage points, and he took the money. I had to explain to him that we were going to do something and that this was going to be for life: “It’s not like you just get 100 quid for this and then that’s the end of it. We’re doing this ourselves – there’s no big, horrible manager.” The whole point of this was that it was a sort of communal thing: a different approach. So, it’s rather nice that we’ve always got little dribs and drabs of money from 801 and always shared the credibility. And everybody’s pleased that it’s coming out now.

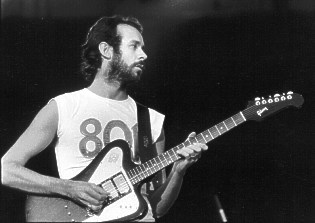

How did you see 801 as different from what you were doing with Roxy?

Well, it was very different because the musical source of all 801 was Eno solo material, my solo material and the material I was doing before Roxy with Quiet Sun, and all that music came from a different area than the Roxy Music music. It came from a different set of source pools, if you like. I think, on balance, that’s true. I mean, from Roxy to 801, obviously there’s a certain consistency with Eno’s use of tape loops and things like that, but really 801 was drawing on a slightly different set of influences there.

Was there an idea of getting back to basics? Away from the glitz of Roxy, to a more straightforward approach?

There was no thought about the image side of it at all really, whereas Roxy was all about image and music. Rock’n’roll is at its most potent and powerful when it combines music and image, but I guess that 801 was more about music and ideas, musical ideas, rather than the visual side, really. We had a strong identity in the 801 – being 801, having a band name – but it wasn’t so visual.

Whose idea was it to use the famous number – 801 – from “The True Wheel” as the band name?

As I said, we were down at this cottage, me, Eno, Bill and Ian and that’s when the whole thing was hatched and that’s when the name was decided on. In the booklet that comes with the album, you’ll see the whole explanation of where it comes from. It’s finally revealed – well, it’s an attempt to reveal it. Also, in one of the notebooks that I photocopied, you’ll see, in Eno’s writing in fact, a series of names that we were thinking of for this project and one of them says “the 801.” Some other possible names were Flight 19, the Central Shaft, the Host, the Bridge, Reactor, Sponge [laughs], Anarchist, hmmm…. The booklet is a thing of beauty. I’m very proud of it. There’s all sorts of nooks and crannies in it. It’s 50 pages, with lots of handwritten things from the time when we were going through it.

Was there any plan to include “The True Wheel” in the live set? It could have been your anthem.

There was, actually, but I don’t think it cut it. It’s a bit wimpy…that chorus! I don’t think it was hard enough, especially if you’re going to play “Third Uncle” – you don’t want to be playing “The True Wheel.” It might sound a bit fey, somehow.

Were you very aware of punk? This was 1976 and forming an prog/art-rock supergroup could have got you burned at the stake.

Yeah, I’d actually be interested to look at the dates of when the Sex Pistols played that so-called seminal gig at the 100 Club….

It was September 20th, 1976.

So in fact punk hadn’t made its presence fully felt by then, but give it six more months and there’s no way we’d have dared to do 801, without a fear of getting beaten up! But then, having said that, you suddenly find out later that people like the Sex Pistols and Johnny Rotten loved Roxy and we never knew. People said that the punks liked us but we thought, “What? Surely that can’t be right!” We were all scared we’d get beaten up. But people said, “No, they loved you!”

Lydon was one of the few punks who actually fessed up to liking art rock and progressive rock.

Well apparently, Sid [Vicious] went up to Andy Mackay once and said, “Yeah, Roxy Music – fucking great! Except for that Bryan Ferry – he’s a real cunt” [laughs]. We were like, “Phew!” – mopping our brows in relief. But, no, you’re right, given a bit more time, we probably wouldn’t have dared with 801.

When you look at a song like Eno’s “Third Uncle,” though, that was ahead of the curve, punk avant la lettre, really.

Yeah, thinking about it, exactly. That was definitely ahead of its time. And with Roxy we used to say – I don’t know whether anyone believed us – that we started with exactly the same conceptual attitude as punk: you didn’t have to be able to play your instrument particularly well; as long as you had good ideas and a lot of energy, you could be successful. And, obviously, there was the visual side as well. As long as you looked good and had ideas. So we did see some kind of relationship between Roxy and what punk was all about, because when we started with Roxy we got a lot of stick from professional musicians saying, “Who the hell are these people? They only know a couple of chords and can hardly play. What are they doing?”

801 featured several rather accomplished musicians and one famous non-musician. Did this produce interesting creative tension?

It created hilarious situations, like with “East of Asteroid,” where you’d get someone like Eno, who’s not used to playing in funny time signatures, and then you’d get people like Simon Phillips and, particularly, Francis Monkman, who went to the Royal Academy of Music. “East of Asteroid” starts in 13/8. And Eno only had to come and play one note, but getting him to play at the beginning of a 13/8 bar was a bit of a struggle. Me, I span the two things: I’m into playing rough old rock’n’roll as well as having had the training in the other area. So there was a little bit of “Oh, fuck off”. There was a lot of tension, actually. The thing is, we rehearsed a hell of a lot, for about six weeks, and only did three gigs and, by the end, it was a miracle, probably, that we even did the three gigs, because by that stage the musician versus anti-musician thing had become a bit of a problem.

Eno came at it with a conceptual, experimental approach – how did that manifest itself?

In his use of instruments and sound effects. He had this tape that he put on at the start of “Tomorrow Never Knows” that he’d pre-made from a mixture of radio and backwards stuff, and he just pressed play on the tape recorder at the beginning of that number. And every time we played the song, it would come in in a different place. So in effect, he was using prepared-tape on that. On the other, more jazz-rock, proggy rock songs, he’d find a part to play that would be pure Eno stuff against the others, to combat perhaps what he was hearing that he might not have particularly liked. By forcing this other sound, his sound, against it, it created something unusual that was a reaction almost to that other kind of music. So it wasn’t intended to be sympathetic; it was intended to somehow counteract it or obliterate it. It was a series of interesting skirmishes.

With Eno introducing these chance, random elements, did the songs change from performance to performance?

That’s the interesting thing if you listen to the differences between the rehearsal tape and the gig itself. Obviously, where there are verses and singing parts, things are the same, but a lot of the other bits are different. That’s why I thought it would be interesting to put out the second CD, because anyone who’s heard the live album a lot will know roughly what the solos are and they’ll hear a totally different set of stuff now. Not that we’re in the same league as the Beatles, but I think it’s like when you listen to the Beatles’ Anthology and you hear the acoustic version of George Harrison singing “Something” or his demo version; the solo is different and you know the final version of the solo so well that it’s sort of interesting and weird to hear the other version. It’s a real collector’s sort of thing [laughs].

The songs 801 played came largely from your and Eno’s albums. How do you think the 801 performances reinvented them?

Totally. I think it really brought them to life. I think it was a lot more exciting than it was on the original records. One of the reasons was the drumming, because Simon Phillips was and still is an incredible drummer. He was about 18 at the time and he was like a force of nature, a tornado. He was so confident in his playing that it just provided such a rhythmic, grooving sound that you could then take risks. People always say, “You’re only as good as your drummer” – the drummer’s such an important part of any band.

Talking of drummers, you worked with Charles Hayward in Quiet Sun. Was there ever any possibility of his being in 801?

No, and I don’t know why, unless maybe he was doing This Heat by then. I did an album last year with Charles – after the last Quiet Sun album in 1975 – and we played at Ronnie Scott’s for three nights and also went on tour in Poland. Charles has turned into an even better drummer than he was in Quiet Sun. He’s turned into an absolutely fantastic drummer. I don’t know if you’ve seen him recently, but he does a one-man show here supporting lots of trendy young bands, who adore him. He’s mad as a hatter. Seeing him play is an extraordinary thing to behold. I can’t remember why he wasn’t in 801, but I suspect he was doing other things.

During Roxy’s early gigs, Eno processed your guitar as you were playing. Did that happen with 801?

Yes. “Diamond Head” is all going through his gear.

And “Lagrima”?

“Lagrima” too. The beginning. Absolutely. So, yes, 801 did include the types of thing we were doing in the original Roxy and that Eno continued to do through his solo albums. We were trying to accommodate that in the live scenario as well.

Was it disorienting for you to be playing and have Eno simultaneously treating your sound?

Well, in Roxy, when we very first started up, we had no amps on stage – Eno did the whole thing and he was out in the audience. It was so incredibly unsatisfying that we had to stop it because we felt like a bunch of complete muppets. And we couldn’t hear anything, either. It was like an Eno-fest out the front, but it was also fantastic, of course. I certainly hadn’t seen anyone else doing that before Roxy. It was “Ladytron” particularly, that was the track where he used to do it. It used to end up with just him and me, him treating my guitar and it going through all these Revox tape recorders, with him slowing them down and speeding them up. And by the end of that number, I was literally just strumming the thing. I didn’t really recognize what was coming out of the speakers. It was actually a bit of fun at the time, as well. So, no, I didn’t really mind.

Was the 801 set actually conceived and constructed with a live album in mind?

No, it was just that I suddenly thought, “Hey, we’re only going to be doing three gigs – why don’t we record one of them?” If you think about it, it was quite bold at the time. At that time, recording a gig was a big deal: getting the mobile recording studio to come and park up outside. I’m amazed they let us do it!

Do you recall who suggested the cover versions that 801 did?

It could have been Ian MacCormick who suggested “Tomorrow Never Knows” and I think “You Really Got Me” was me.

Why those particular songs?

At that time, “You Really Got Me” hadn’t yet been played by 50 million karaoke bands. It seems incredible, but at the time it wasn’t that long, only ten years or so, since it’d come out, and it was one of my favorite songs. So we had no problem with covering it: it was before every Tom, Dick and Harry, Van Halen and everybody else did it. And we did “Tomorrow Never Knows” because we were all Beatles fans, but also obviously because of the experimental nature of the song. It was totally correct conceptually that it should be the vehicle to deposit all that combination of musicality and sounds. It’s like, you’d always say to a new band, “Do a cover,” because by doing a cover you learn something about what you’re about, your style. If you do a cover in your style, you learn something about yourselves. And, you know, when I listen to “Tomorrow Never Knows,” all the ingredients of what 801 is about are in that track. Although it’s by somebody else, I could relate it to all the other bits on that record, to our own songs in some strange way.

What would you say are those ingredients of your version of “Tomorrow Never Knows” that embody 801’s overall aesthetic?

Well, you’ve got the random element of the tape that comes in at certain points. You’ve got the sort of riff-playing, the sort of prog rock-y bit, and you’ve got the harmony singing. You’ve got a bit of slide guitar solo, or actually that’s me pretending to play slide guitar. You’ve got the amazing drum build-up at the beginning. You’ve got the demonstration of Francis’s technical abilities, but applied in almost a raga-type fashion. There’s also Bill’s bass playing, coming via Jack Bruce – using the bass as a lead guitar. And I’m just playing a tape loop-type effect rather than the reverse, where I should be soloing away like mad and Bill should just be holding it down – but he’s not that kind of person. You can’t hold Bill down [laughs]. So you’ve got all the people introducing their wares, if you like – laying out the table there, right at the beginning of the record.

You consider 801 Live one of the most prestigious projects you’ve been part of. Why is it such a storied record?

It was just one of those times in life where everything comes together for a brief moment, with the right musicians coming together at the right time. It was designed to last a very short amount of time, and it couldn’t have gone on any longer: you know, there were different camps and people were going to kill each other [laughs]. It was a bit of a weird experiment. I think we all left the building quickly before the whole place set on fire and self-destructed.

(Interview by Wilson Neate)